Anecdotal reports across the Higher Education sector in the UK suggest there has been a rapid recent expansion in the numbers of students taking Foundation Programmes, which combine study of academic subjects with study of EAP, to prepare for undergraduate study. What seems new is that the student population is more diverse, including both international students who have learned English as a foreign language, international students following English-medium instruction (EMI) in their home countries, and students in the UK whose English is an additional spoken language (EAL). This third group may be the first in their family to go to university so they lack the cultural capital that parents educated to tertiary level can pass to their children. These students may have short attention spans and need considerable pastoral support in understanding how to study effectively. It can be argued that each of these three groups have different language learning and study skills needs yet they are often taught together in EAP classrooms, representing a significant challenge in course design. In this post I want to think about syllabus design which enables these diverse groups to learn together in one classroom.

I’m no longer teaching or designing EAP courses so I’m reflecting back to the two coursebooks in the Access EAP series that I wrote with Sue Argent. These were published by Garnet Education in 2010 (lower level Foundations) and 2013 (higher level Frameworks). We intended these to be the instantiation of the principles we set out in EAP Essentials (2018, 2nd edition). At the time, we considered some of the same issues that are confronting Foundation Programmes today: short attention spans, mixture of language proficiency and history of language learning, lack of cultural capital, i.e. knowing what university is like and how to study there. Sue and I were looking for universal concepts, in both language and study skills, that would be relevant for this diverse group.

Is your syllabus like this…

… or like this?

It’s worth considering for a moment how coherent your Foundation Programme and the syllabuses in its various modules are. Can your students see overall patterns in your course design weaving together as in tartan? Or is it more like a crazy patchwork, a ragbag of topics and skills with little overall coherence? Do you state the underpinning principles of progression and recycling of course content across modules in ways that are easy for students to understand? Is the content of subject modules integrated into your language modules and vice-versa or is there simply a loose skills connection?

A recent critique of ELT coursebooks (Jordan & Gray 2019) notes that they have largely fallen back towards grammar-based syllabuses with Presentation-Practice-Production methodology. This no longer accords with Second Language Acquisition Research, which ‘strongly suggests that students learn faster and better if teachers spend the majority of classroom time giving students scaffolded opportunities to engage in communication activities with each other about matters of mutual interest, focusing on meaning’ (Jordan & Gray 2019: 441). The article recommends other syllabus types such as process or task-based syllabuses. These are certainly more appropriate in EAP courses but dealing with questions of grammar, pronunciation, lexis or collocation as the need arises is complex for a diverse student group.

Sue and I based our coursebook syllabus on a Systemic Functional Linguistics (SFL) approach, setting Field as a fictional institution, Gateway University, in which three students progress through their studies in the first semester. This personalises the content for Foundation students as they are asked to reflect on their performance compared to the Gateway students. We adopted a task-based syllabus to introduce students to the tasks they will perform in their first semester, but the underpinning design principle was functional. In Access EAP: Foundations, each function was linked to a new situation, e.g., Freshers’ Week (describing shape position and movement), New Routines (describing process), In the Library (comparing and contrasting). This type of syllabus follows a clear progression through describing and explaining to persuading. It also has the benefit of introducing a new way to think about language, which is relevant for each of the different groups of international, EMI or EAL students. This level of language analysis is also universal across disciplines, which all define, compare and argue using similar language structures.

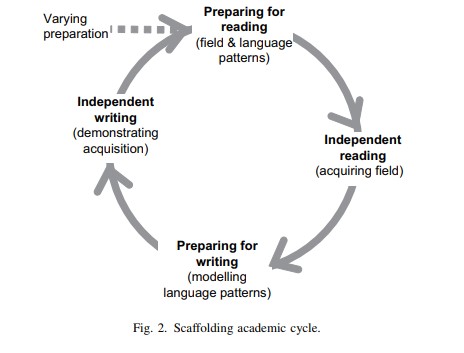

Alongside the presentation of functional language, we used an integrated skills approach: Scaffolding Academic Literacy (Rose et al., 2008), which has been demonstrated to be a promising approach for students from non-traditional backgrounds. By choosing texts related to the disciplines our fictional students were studying (Computer Science, Business, Environmental Science), we could demonstrate how to read, listen, speak and write in these and other disciplines, using the functional language we presented in each unit. Rather than give vague instructions to skim/scan a text for ideas, the scaffolding approach identifies position cues in a text, e.g. the language for definitions, that provide key information. Once students have engaged with the content of a text in academic ways, they identify functional language they can use in a writing task.

We introduced the concept of a Triple A student: Adventurous, Active and Aware, one who is prepared to take risks, try out new ideas, make mistakes, reflect and learn from these. All of our three fictional students (one home student and two international students) experienced problems that are typical at the start of university study. By aligning themselves with the students in the coursebook, Foundation students come to understand what leads to success.

The main argument against this type of course design is that it requires considerable engagement, on the part of course designers, with a complex theory of language (SFL) so that a topics and skills approach is easier. It also requires a lot of concentration from students with short attention spans. These are the kinds of justifications Jordan and Gray (2019) identified in their analysis and critique of ELT coursebooks. Surely Foundation students deserve better.

Jordan, G. & Gray, H. (October 2019) We need to talk about coursebooks. ELT Journal, Point and Counterpoint, 73/4 pp. 438 – 446; doi:10.1093/elt/ccz038

D. Rose, D. et al. (2008). Scaffolding academic literacy with indigenous health sciences students: An evaluative study. Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 7 pp.165 – 179; doi:10.1016/j.jeap.2008.05.004

Yes I agree with all the approaches explained here and feel that tying programmes and syllabuses to topics and skills and focusing only on grammar is a disservice to both students and teachers. Once you look at course and syllabus design through an SFL and corpus-based focus it is transformative for both students and teachers. I can’t count the number of times I have had the comment “Why did no-one tell me this before?” – not only in the classroom but with the experienced researchers I work with at present, editing their books and papers and explaining the problems in terms of the reader-oriented focus that is enabled by a SFL functional approach. The word FUNCTIONAL is a clue that all writing has a purpose and therefore an end-user — the reader! Conventional grammatically based approaches leave students feeling that all they need to do to succeed is to obey the preferences of a set of arbitrary anonymous rule makers. This image of the anonymous and unchallenged rule makers also means they are not critically equipped to deal with the challenge -posed by inadequate resources such as simplistic online dictionaries and commercially driven grammar checkers, which only add to their problems rather than solving them.

LikeLiked by 1 person